The language we use to describe nature is disappearing. So is essential human connection to nature.

Poetic words often used to describe nature are slowly being erased from online databases–and our knowledge–across the world.

Take adjectives such as stately, noble, lofty. Take nouns such as bluebell, honeysuckle, magpie, moss, turnip, pasture, porridge. When was the last time you encountered any of them?

For me, until I read this article, it felt like forever since I had seen those words as a child who loved reading storybooks.

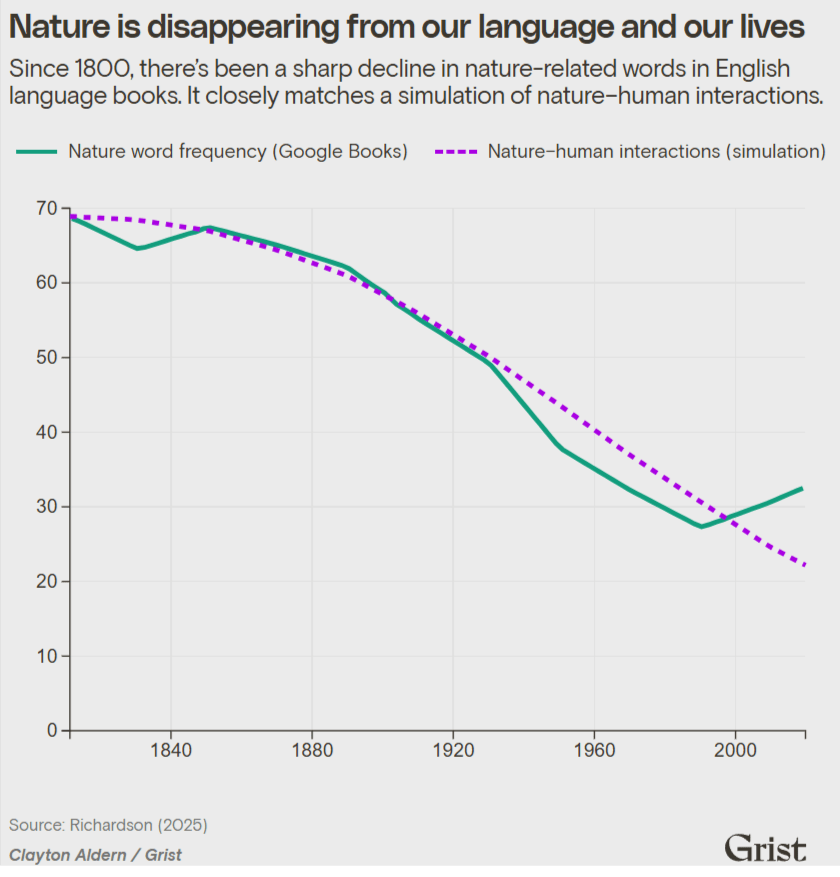

Indeed, according to a 2025 research study published in the journal Earth, nature words have been disappearing. The decline became particularly prominent after 1850, around the time of rapid industrialization and urbanization. In 1990, there was a record 60.6% decline in the use of natural words. Why is this important?

In 2007, over one hundred words were removed from the new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary. In response, a group of 28 writers led by Margaret Atwood published a critical open letter to the Oxford University Press. The letter expressed the urgent necessity that kids connect with nature, because strong connectedness with nature positively correlates with social-emotional development, well-being, and health. On a fundamental level, this must be ensured through thoughtful cultivation of culture and use of language.

“The research evidence showing the links between natural play and wellbeing; and between disconnection from nature and social ills, is mounting…We believe that a deliberate and publicised decision to restore some of the most important nature words would be a tremendous cultural signal and message of support for natural childhood.”

Margaret Atwood et al.

The problem extends far beyond disappearing nature words. The language we use when discussing nature has changed significantly, which in turn reflects our growing detachment from nature. This cultural shift represents a major underlying cause of many environmental crises, as well as missed opportunities to reap the myriad of benefits of strong nature connectedness.

Too often, we consider ourselves as apart from, or even above, nature. Too often, we carry the mindset that we, as humans, exist as a separate entity compared to nature and wildlife, rather than being interconnected with this dynamic ecosystem that gives us life.

“As our language around forests became less reverent,…people began using more scientific and economic terms to describe trees. In other words, people began viewing forests as something from which to extract value, not inspiration.”

Kate Yoder, Grist Climate News

As French philosopher René Descartes established, this sense of detachment between the self and community inherently leads to a more alien approach to society and nature. Many Indigenous cultures, especially those of the Pacific island, combat this regression through their longstanding tradition of environmental sustainability, kinship, and stewardship.

An important part of this tradition is grounded in their language, which contains ecological knowledge and implies a deep metaphysical connection. For example, the Hawaiian word for “land” – “Āina” – translates to “that which feeds and sustains.” The meaning is not only literal but also spiritual and emotional. Āina nourishes fully and with love.

By understanding cultures that are attuned to nature, we can recognize just how important culture and language are in evoking appreciation, respect, and care for nature.

There is still hope for a cultural shift. As cited by the same Earth paper, the decline in the use of natural words and in nature connectedness eased slightly from 60.6% in 1990 to 52.4% in 2020.

In the face of environmental destruction, we can all learn from Indigenous languages to salvage our disappearing words and to reestablish the crucial connection between nature and people. In the end, people are nature, too. By caring for our environment, we safeguard our own health and lives.

Leave a comment